Turkey Vultures

Turkey Vultures are in the family Cathartidae, also known as the “New World Vultures”. That family also includes California Condors, but Turkey Vultures are much smaller in size compared to condors, with a wingspan of about 5.5 feet (condor wings stretch over 9 feet across).

Turkey Vultures have the largest nares (nostrils) of the New World Vultures, and like condors there is no septum dividing the nasal passages – so you can see right through from one side to the other! This allows more scent molecules to enter the nasal cavity and is also much easier to keep clean.

Turkey vultures are obligate scavengers, which means they only feed on dead animals. Their incredible sense of smell can detect dilute volatile gasses coming from the bodies of dead animals, even while soaring hundreds of feet in the air. Turkey Vultures do not kill their own food, so their sharp beaks are only used for tearing open tough hides and shredding large sections of flesh on animals that are already dead.

Photo Credit: Nicollet Overby (all rights reserved)

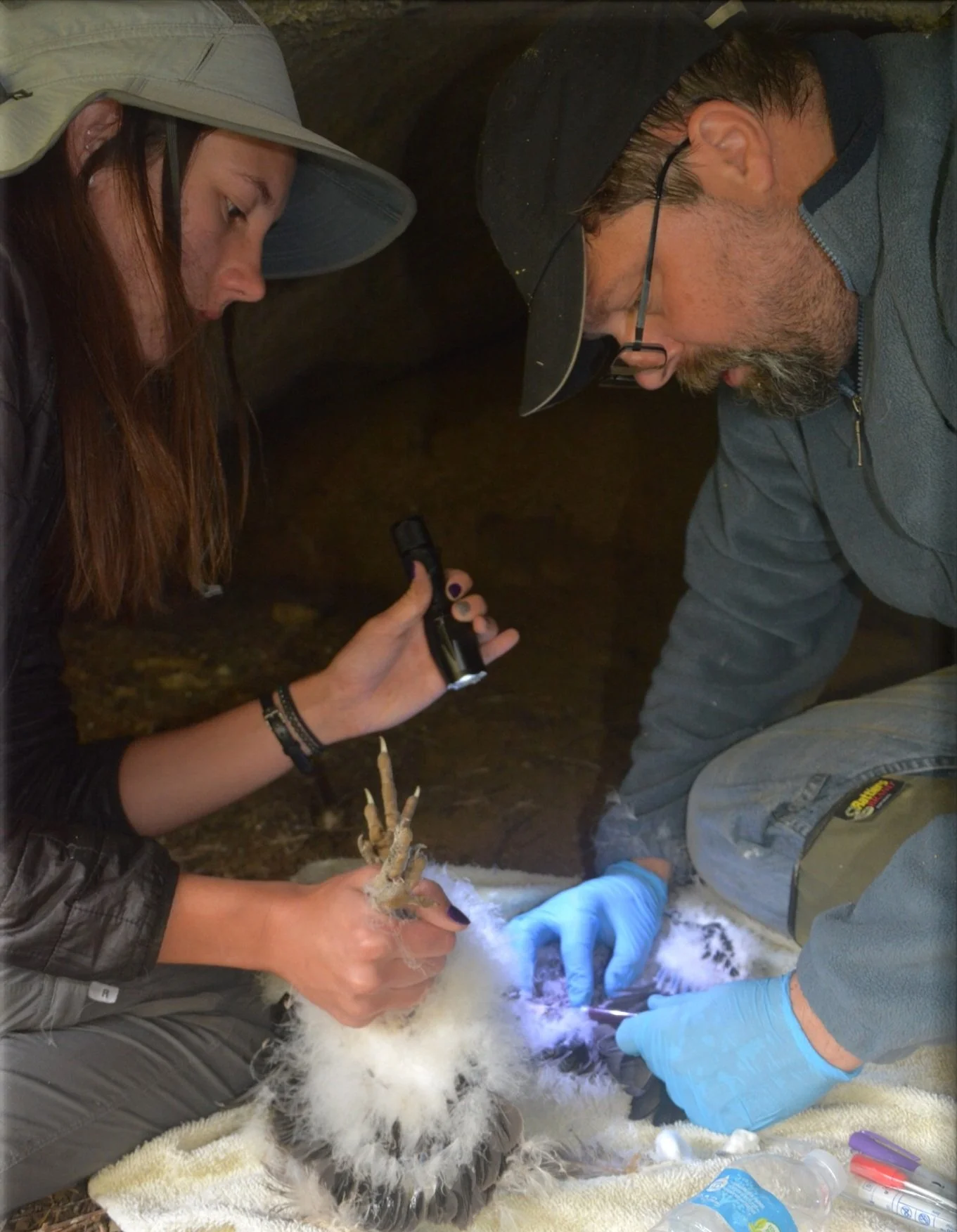

Photo credit: Pete Bloom (taken during a 2020 trapping and tagging project. All rights reserved)

Turkey vultures are widely distributed around the world, and are fairly ubiquitous throughout California. Pete Bloom has tagged nearly 500 individual Turkey Vultures since 2005.

Nests are typically crevices in rock formations or caves, and no nesting materials (i.e. sticks or grasses) are used. Only one brood are raised during the nesting season, consisting of one or two chicks.

The longevity record for wild Turkey Vultures belongs to tag “20” who was tagged in 1997 by Pete Bloom, and was last seen in 2019 at the age of 23 (see “Historical Research” section below).

Photo Credit: Nicollet Overby (all rights reserved)

Photo Credit: Nicollet Overby (all rights reserved)

A Turkey Vulture typically weighs between 2-4 lbs., and their lightweight bodies combined with their large wingspan enables them to soar very high for very long distances. They can travel up to 200 miles per day, soaring on thermal updrafts, at heights of up to 20,000 feet.

They have a very robust immune system, and can eat carcasses contaminated with pathogenic bacteria (i.e. anthrax, botulism, cholera and salmonella, etc.), usually without being affected. This is what makes them “Nature’s Clean-Up Crew”, ensuring these pathogens and bacterium are removed from the environment. But they are vulnerable to certain toxins and chemical agents such as those found in pesticides and rodenticides. They are also susceptible to lead, which can be found in the environment due to human activities such as hunting with lead bullets (if they eat the offal discarded by hunters that contain bullet fragments).

Turkey Vultures can be useful environmental sentinels of lead - they cover extensive surfaces of land while searching for food, they have a large enough blood volume to safely obtain samples, they have a measurable response to lead, and their populations are sufficient in size and relatively stable (they are not threatened or endangered like other large scavenging birds such as condors and eagles).

Photo Credit: Pete Bloom (all rights reserved)

Bloom RESEARCH:

Bloom, P. H., Overby, N., Saggese, M. D., Eagleton, A., Koedel, A. B., Batzloff, H., & Bonisoli-Alquati, A. (2025). Movements of Turkey Vultures Provide Evidence of Nonmigratory Behavior and Natal Philopatry in a Population Breeding in Southwestern California, USA. Journal of Raptor Research, 59(4):jrr2392.

Saggese, M. D., Bloom, P. H., Bonisoli-Alquati, A., Kinyon, G., Overby, N., Koedel, A., ... & Poppenga, R. H. (2024). Turkey Vultures (Cathartes aura) from Southern California are Exposed to Anticoagulant Rodenticides Despite Recent Bans. Journal of Raptor Research, 58(4), 491-498.

Oakley, B. B., Melgarejo, T., Bloom, P. H., Abedi, N., Blumhagen, E., & Saggese, M. D. (2021). Emerging pathogenic Gammaproteobacteria Wohlfahrtiimonas chitiniclastica and Ignatzschineria species in a Turkey Vulture (Cathartes aura). Journal of Avian Medicine and Surgery, 35(3), 280-289.

Bloom, P. H., Papp, J. M., Saggese, M. D., & Gresham, A. M. (2019). A simple, effective and portable modified walk-in turkey vulture trap. North American Bird Bander, 44(4), 5.

Kelly, T. R., Bloom, P. H., Torres, S. G., Hernandez, Y. Z., Poppenga, R. H., Boyce, W. M., & Johnson, C. K. (2011). Impact of the California lead ammunition ban on reducing lead exposure in golden eagles and turkey vultures. PLoS One, 6(4), e17656.

Houston C. S., Bloom P. H. 2005. Turkey vulture marking history: The switch from leg bands to patagial tags. North American Bird Bander, 30(2), 59–64.

Henckel, R. E. (1976). Turkey Vulture banding problem. North American bird bander, 1(3), 7.

Photos above by Pete Bloom (all rights reserved) with the exception of the final image of “LA” in Yuma, used with permission by the photographer.

Historical RESEARCH

Turkey Vulture, California Condor, and Common Ravens at a carcass (Photo Credit: Pete Bloom - all rights reserved)

Photo credit: Ryan Wood (Orange County, CA) - all rights reserved, used with permission.

During the 1980’s, Pete Bloom led the Condor Research Team, working to save wild California Condors. Since lead ammunition was a known cause of poisoning in condors, a suitable ammunition replacement needed to be found; two possibilities were copper and tungsten-tin-bismuth (TTB). In 1997, graduate student Ramon Valencia from California State University Long Beach, with the help of several advisors (including Pete Bloom), arranged a study where 30 Turkey Vultures were trapped and kept in captivity under veterinary care for a period of six months, to evaluate the potential effects of these lead-replacement materials, using two test groups compared to a control group. His study revealed that CBC and chemistry panels had no significant differences, and no cellular toxicity was found between the control and test groups. Copper was found not to concentrate in the blood sera, although tin concentrations became elevated for those treated with TTB. All of the Turkey Vultures used in the study were tagged with Bloom’s white patagial tags showing a black two-digit code before being released at the end of the study period. At least one Turkey Vulture from this 1997 study was known to still be alive as of 2019, as shown in the photo to the right. The tag was able to definitively identify and age this bird, which is why these markers are so important to research, and the sightings of these markers reported by the public are also incredibly important and appreciated.

Dissertation: Valencia, R. M. (2003). An assessment of the toxicological effects of ingested copper and tungsten-tin-composite (TTC) bullets on the California condor (Gymnogyps californianus) using the turkey vulture (Cathartes aura) as a surrogate species. California State University, Long Beach.

For further reading on how you can help contribute to our research

by reporting Turkey Vulture tag sightings, see our blog post on

the Bloom Biological Inc. website: Wing Tags on Turkey Vultures.

Bloom Biological Inc. is Pete Bloom’s biological consulting company, which is now a part of the Endemic Environmental Services family. “By uniting Bloom’s legacy with Endemic, ICRE, and Cambriate, the partnership strengthens Endemic’s mission of Conservation at Scale through science, mentorship, and innovative research.”

Bloom Research Inc. is maintained as a separate non-profit entity to continue Pete’s long-term raptor research.