Rodenticides - Bloom Research:

Saggese, M. D., Bloom, P. H., Bonisoli-Alquati, A., Kinyon, G., Overby, N., Koedel, A., ... & Poppenga, R. H. (2024). Turkey Vultures (Cathartes aura) from Southern California are Exposed to Anticoagulant Rodenticides Despite Recent Bans. Journal of Raptor Research, 58(4), 491-498.

Rodent Facts:

L. Prang & Co. (Public domain)

Approximately 40% of all mammals on earth fall under the order Rodentia. The defining characteristic of all rodents is that they have one pair of both upper and lower incisors that grow continuously. Ground squirrels, tree squirrels, voles, mice, rats, porcupines, chipmunks, beavers, and prairie dogs are all examples of well-known animals classified as “rodents”.

Rodents are an important part of wild ecosystems. They become problematic in human occupied settings due to a reduction of natural predators, an abundance of food sources (supplied knowingly or unknowingly by humans, i.e. dumpsters, bird feeders, compost piles, crop fields and storage, etc.), and an abundance of hiding and nesting locations within human structures.

There are 16 genera of mice and rats found in North America, and most play the important role of seed dispersers within their wild habitats. They also help maintain carnivore biodiversity as one of the critical sources of food for medium-sized predators (hawks, owls, foxes, snakes, coyotes, etc.). They are incredibly adaptable and resilient, which is how they continue to thrive even when faced with total destruction of their natural habitat due to human development; they learn to make-do with the new environment, which includes invading human structures and scavenging for food among human refuse.

In the wild, small rodents like mice and rats have a very high rate of predation due to their numerous predators, therefore they have evolved to have rapid reproduction rates to keep wild populations stable. Many species of mice and rats can have up to 10 litters (consisting of 2 - 8 young per litter) every year. When their wild habitats disappear (along with their natural predators), those reproductive rates can quickly cause an otherwise stable population to get out of control very quickly.

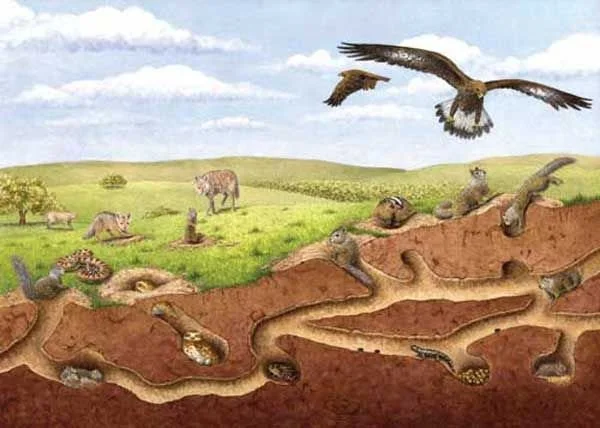

Animals such as snakes and other reptiles, along with some amphibians, rely on abandoned burrows created by rodents like voles and pocket gophers.

On the west coast, another burrowing rodent - California Ground Squirrels - can wreak havoc within developed areas like parks, levees, and crop fields. But they are also an integral part of their habitat, relied upon by other wildlife such as Burrowing Owls, who repurpose abandoned burrows for themselves. The ground squirrels also provide early predator warnings with alarm calls that the Burrowing Owls have learned to pay attention to. Their continuous burrowing aerates the soil and brings seeds to the surface as they build new burrows, which is beneficial for the plant life which supports the insects and other small animals that Burrowing Owls feed on. When ground squirrels are eradicated due to development, habitat fragmentation, or poison, the Burrowing Owls disappear as well.

Rodenticide Facts:

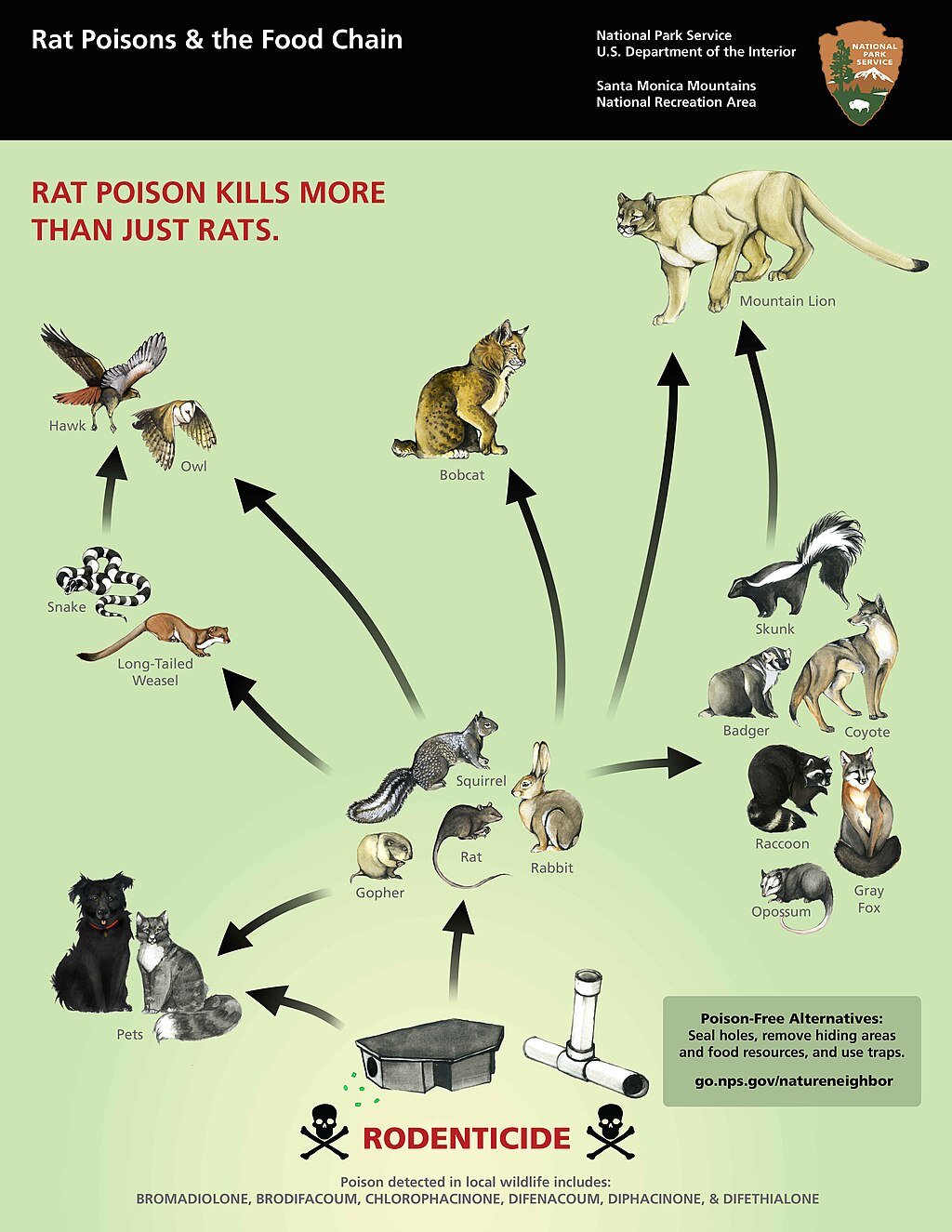

A common misconception is that rodenticides will only kill the rodents who ingest them.

In truth, any animal, including pet dogs and cats, who consumes the poisoned bait will likely die from the effects if not treated at a veterinary hospital immediately.

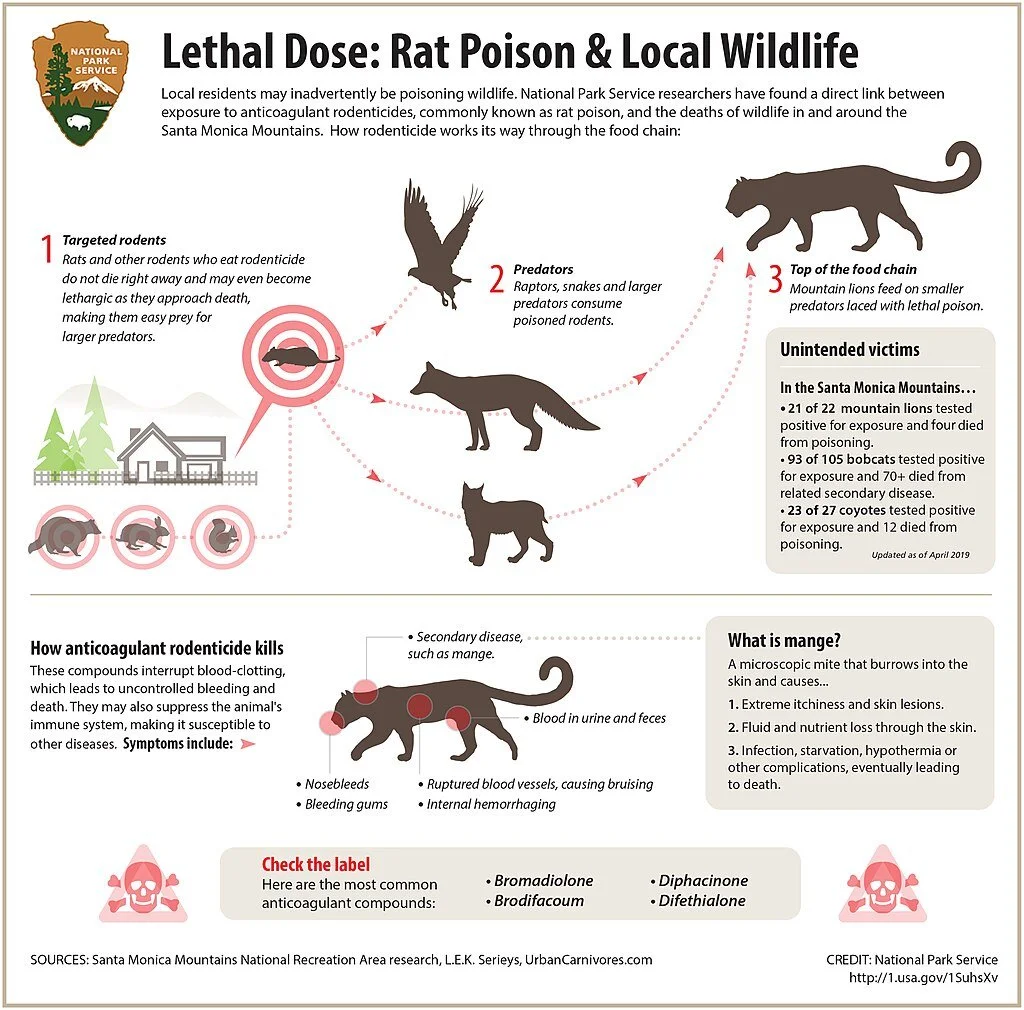

Making sure the bait is only accessible to the target rodent(s) won’t stop other animals from being killed by the poison. After exiting bait stations, the poisoned and slowly dying rodents become easy targets for predators. Unfortunately, when that poisoned rodent is eaten by a predator, that predator can also succumb to the accumulated anticoagulant or other chemical effects.

Clinical signs of anticoagulant rodenticides are massive internal bleeding caused by a loss of vitamin K1 (which is essential for blood clotting); if untreated, death will usually occur within 3 days. This means the poisoned rodent may be able to travel a fair distance in a suffering state before they die.

During nesting season, owls have been known to bring poisoned rodents back to the nest, with the vulnerable owlets dying as a result.

It’s not just raptors that are being affected – other predatory animals are falling victim to the bioaccumulation effects as well. In 2019, a California mountain lion (P-47) fitted with a radio tracker in 2017 was found dead in the Santa Monica Mountains; despite having survived injuries sustained during the intense Woolsey Fire in 2018, he could not overcome the effects of secondary rodenticide poisoning. Six different anticoagulant compounds were found in his liver during a necropsy.

In fact, 90% of mountain lions, 88% of bobcats, and 85% of the protected Pacific Fishers tested during research by the California Department of Fish & Wildlife had detectable levels of SGARs (second-generation anticoagulant rodenticides) in their system.

Despite progressively stricter regulations enacted in California since 2019, research has shown that there has not yet been a significant enough reduction in non-target wildlife being affected by SGARs. The California Poison-Free Wildlife Act (AB 2552) went into effect on January 1, 2025; most second-generation as well as first-generation anticoagulant rodenticides (ARs) are now banned in California. But California is so far the only state with legislation restricting these ARs; migratory raptors and other predators can still be exposed when travelling outside of CA.

Not everyone is happy about the new laws in California - farmers, homeowners, business owners, HOA’s etc. feel overwhelmed when they comply and then begin to have issues with rat infestations. Others continue to use old supply despite the bans. More public education is needed to inform people of the best preventative measures to keep rats, mice, and other rodents from taking up residence in the first place.

In 2016, a groundbreaking research project took place in Ventura County. Karl Novak, the county’s dam safety inspector, challenged the status quo and decided to design a study to test whether wild raptors could be as effective as poison to control the ground squirrel population, which were creating dangerous burrows that threatened the integrity of the county’s levee system. By erecting perches for raptors and installing a few owl boxes, he was able to show that the burrows had been reduced by 50% in areas patrolled by hunting raptors, when compared with sites still utilizing rodenticide. Not only was this method safer, it turned out to be cheaper too, with savings estimated at $7,400 per levee mile. Another study by Matthew Johnson with Humboldt State University (see video above), has shown that Barn Owl families in California’s Napa County can consume up to 1,000 rodents per breeding cycle, which can really add up considering Barn Owls may have more than one clutch per year. A similar study by Richard Raid (University of Florida) in the Everglades Agricultural Area of Florida (see video below) indicates that the area now has among the highest density of barn owls in North America, and some of the agricultural producers have reportedly ceased using chemical rodenticides.

There are many ways for people to discourage and prevent unwanted rodent infestations in urban, suburban, and rural areas. Some excellent resources for deterring, excluding, and repelling rodents include:

Please note: “glue traps” are not a safe, effective, or humane alternative to chemical or anticoagulant rodenticides!

A preliminary study done in Los Angeles, CA has shown promising results for a new “rat birth control”.

Additional Publications For Further Reading:

Cooke, R., Whiteley, P., Death, C., Weston, M. A., Carter, N., Scammell, K., ... & White, J. G. (2023). Silent killers? The widespread exposure of predatory nocturnal birds to anticoagulant rodenticides. Science of the Total Environment, 904, 166293.

Nakayama, S. M., Morita, A., Ikenaka, Y., Mizukawa, H., & Ishizuka, M. (2019). A review: poisoning by anticoagulant rodenticides in non-target animals globally. Journal of Veterinary Medical Science, 81(2), 298-313.

Vyas, N. B. (2017). Rodenticide incidents of exposure and adverse effects on non-raptor birds. Science of the Total Environment, 609, 68-76.

Hindmarch, S., & Elliott, J. E. (2017). Ecological factors driving uptake of anticoagulant rodenticides in predators. In Anticoagulant rodenticides and wildlife (pp. 229-258). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Rattner, B. A., Lazarus, R. S., Elliott, J. E., Shore, R. F., & van den Brink, N. (2014). Adverse Outcome Pathway and Risks of Anticoagulant Rodenticides to Predatory Wildlife. (USGS)

DeClementi, C., & Sobczak, B. R. (2012). Common rodenticide toxicoses in small animals. Veterinary Clinics: Small Animal Practice, 42(2), 349-360.