Turkey Vultures

(Cathartes aura)

Turkey Vultures are in the family Cathartidae, also known as the “New World Vultures”. That family also includes California Condors, but Turkey Vultures are much smaller in size compared to condors, with a wingspan of about 5.5 feet (condor wings stretch over 9 feet across).

They often catch atmospheric updrafts, known as “thermals”; as the ground is warmed by the sun, the air above the ground begins to heat as well, creating a convective current that transfers heat vertically through the atmosphere. Think of a thermal as a bird’s “cruise control” – since the heat in the air is doing all the work to lift them in the atmosphere, they don’t have to expend energy by flapping their wings, they can just soar. The bigger the wings, the better the lift and the farther they can soar.

A Turkey Vulture typically weighs between 2-4 lbs., and their lightweight bodies combined with their large wingspan enables them to soar very high for very long distances. They can travel up to 200 miles per day, soaring on thermal updrafts, at heights of up to 20,000 feet.

Turkey Vultures have the largest nares (nostrils) of the New World Vultures, and like condors there is no septum dividing the nasal passages – so you can see right through from one side to the other! This allows more scent molecules to enter the nasal cavity and is also much easier to keep clean. In 2017, a study proved that Turkey Vultures have a significantly larger olfactory bulb (the brain structure that receives information detected within the nasal cavity) relative to brain volume, and more mitral cells (neurons that process and send olfactory information to other parts of the brain) than any other avian species previously measured.

Turkey vultures are obligate scavengers, which means they only feed on dead animals. Their incredible sense of smell can detect dilute volatile gasses coming from the bodies of dead animals, even while soaring hundreds of feet in the air. Turkey Vultures do not kill their own food, so their sharp beaks are only used for tearing open tough hides and shredding large sections of flesh on animals that are already dead.

They have a very robust immune system, and can eat carcasses contaminated with pathogenic bacteria (i.e. anthrax, botulism, cholera and salmonella, etc.), usually without being affected. This is what makes them “Nature’s Clean-Up Crew”, ensuring these pathogens and bacterium are removed from the environment. But they are vulnerable to certain toxins and chemical agents such as those found in pesticides and rodenticides. They are also susceptible to lead, which can be found in the environment due to human activities such as hunting with lead bullets (if they eat the offal discarded by hunters that contain bullet fragments).

Turkey Vultures can be useful environmental sentinels of lead - they cover extensive surfaces of land while searching for food, they have a large enough blood volume to safely obtain samples, they have a measurable response to lead, and their populations are sufficient in size and relatively stable (they are not threatened or endangered like other large scavenging birds such as condors and eagles).

Unlike other raptors, who have large, strong, curved talons to help with catching and killing prey, Turkey Vultures have long toes with flatter, more blunt talons which are better for standing on the ground. They have featherless legs, and engage in a body function called “urohidrosis”, which most simply means they urinate on their legs as a cooling method. The eliminated waste contains properties that also helps get rid of any bacteria that may be on their skin from walking through rotting carrion on a regular basis.

Most birds that are marked for research receive a metal leg band that is sized appropriately for the species and has a unique code stamped into the metal. These metal bands are issued by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) to permitted researchers. Some birds may also receive an additional plastic or metal color band with a larger code that allows researchers to observe the bird from a distance and still be able to identify it (this reduces the need for re-trapping, thereby reducing stress for the bird). Initially, leg bands were used on Turkey Vultures, but in 1976, a bird bander named Ed Henckel wrote a short communication in the publication North American Bird Bander explaining that those leg bands would often become encrusted with damaging cement-like concretions from a build-up of urates (the white stuff you see in bird “poop”), and he noted several serious injuries caused by the leg bands on Turkey Vultures. Some researchers had started adding wing tags to vultures as early as 1970, and after Henckel’s publication, wing tags became the norm. This is also why you will see wing tags on condors and other vultures.

Every researcher who bands and tags birds must go through special training and must apprentice with and receive recommendation from a permitted master bander in order to apply for their own permit. When applied properly, the leg bands and wing tags will not bother or injure the birds. Pete received his first permit in 1970, and has been banding and tagging birds for more than 50 consecutive years now. Every permitted bander with authorization to place wing tags on raptors is allocated a specific tag color and code combinations. Although some tags have codes that appear to be abbreviations or acronyms, the codes are arbitrarily assigned and have no purpose except to identify that unique individual at a later date. Pete Bloom’s tags are white with black letters and/or numbers.

Turkey vultures are widely distributed around the world, and are fairly ubiquitous throughout California, with both resident and migratory populations. Pete Bloom has tagged nearly 500 individual Turkey Vultures, mostly in southern California, since 2005.

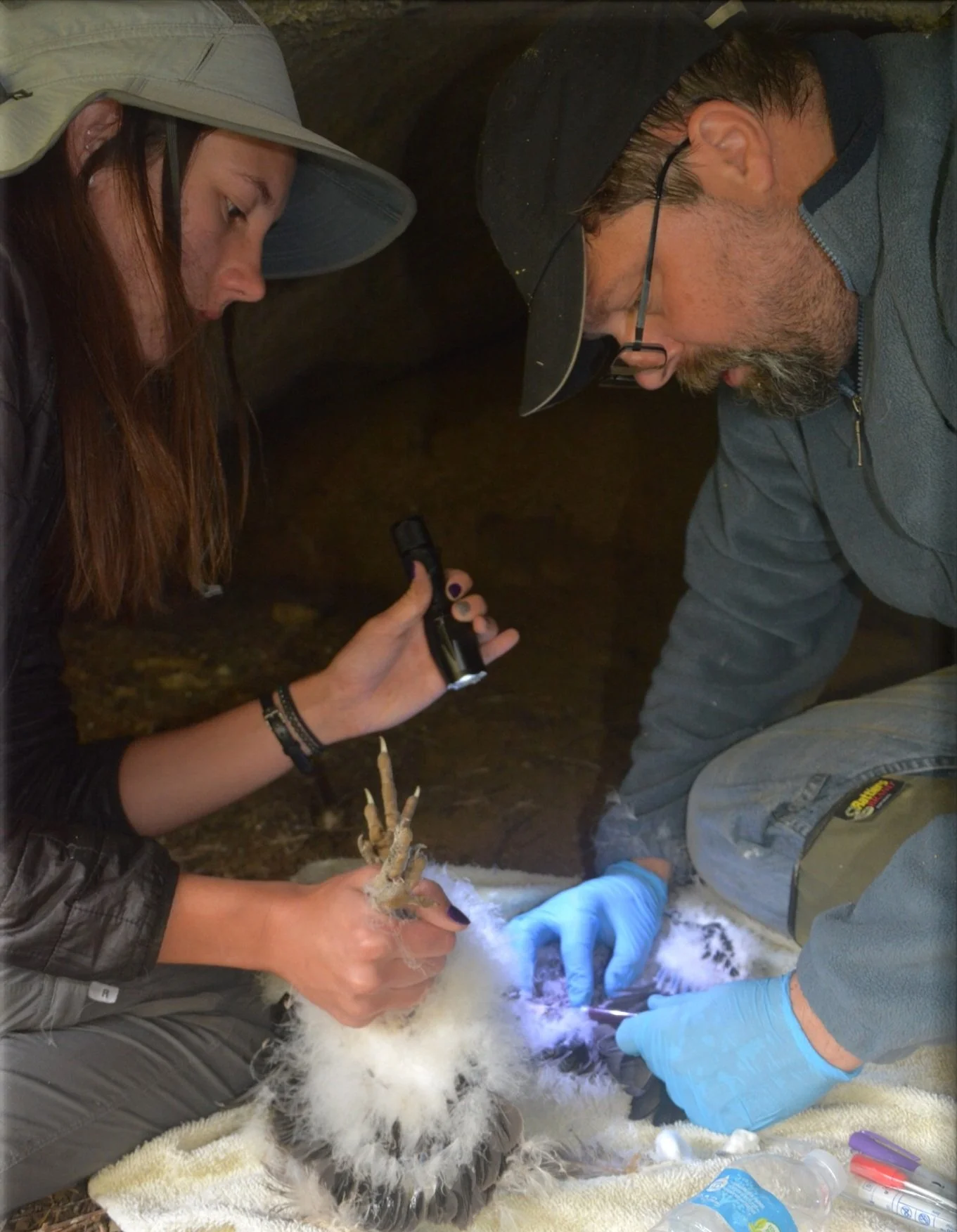

Turkey Vulture chicks are tagged whenever nests are discovered, so that we can study movements such as natal and breeding dispersal. Nests are typically crevices in rock formations or caves, and no nesting materials (i.e. sticks or grasses) are used. Only one brood are raised during the nesting season, consisting of one or two chicks.

The longevity record for wild Turkey Vultures belongs to tag “20” who was tagged in 1997 by Pete Bloom, and was last seen in 2019 at the age of 23 (see “Historical Research” section below).

Photo Credit: Nicollet Overby (all rights reserved)

A Turkey Vulture stretching their wings full length in the early morning sun (“thermoregulating”) – this increases the surface area of their bodies, and helps them to warm up quickly after a cool night or dry off from rain or overnight dew.

Photo Credit: Nicollet Overby (all rights reserved)

Assessing beak color is one of the ways used to age a Turkey Vulture at the time of capture. They slowly lose the black coloration over time, until the beak is fully white around age three.

Photo credit: Alexandra Eagleton (All rights reserved)

With suburban development increasing, roadkill is a common but dangerous food source for the Turkey Vulture.

Photo Credit: Nicollet Overby (all rights reserved)

Turkey Vultures gather at a drained pond in Southern California, where dozens of fish had been stranded and died.

Photo Credit: Nicollet Overby (all rights reserved)

A previously tagged Turkey Vulture spotted in Orange County, CA (2021). This vulture was seen in the same location where it was tagged in 2016, and has been encountered several times over the past few years, always in Orange County.

Photo Credit: Dr. Miguel D. Saggese, used with permission.

Hal Batzloff, a long-time and dependable volunteer, releases a tagged Turkey Vulture in 2020.

Two chicks in their cave nest prior to having tags placed on their wings.

Photo Credit: Pete Bloom (all rights reserved)

What should you do if you see a bird with a wing tag? Just like with banded birds, any sightings within North America should be reported to the USGS Bird Banding Lab, which can be done online at www.reportband.gov. They maintain a centralized database of all the banded and tagged birds, so submitting your sighting to them will ensure the correct researcher receives an official record of your encounter, and preserves the data for future researchers. After reporting the band and/or tag, you will receive a certificate of appreciation, which will include some basic details of when and where the bird was tagged, age of the bird, etc. We rely on the public to provide the majority of our banded and tagged bird re-sights. Since vultures (and condors) don’t have leg bands, the way to report them is a little different than other regularly banded birds.

To report a wing tag, you will need the following information:

The wing tag code; please note, code may be all numbers, all letters, or alpha-numeric. There may also be symbols such as a dot below the characters - be sure to report all characters including any symbols (if any).

Tag Color

Which wing - Right and/or Left

Date and location of bird sighting (if you do not have exact coordinates, it is helpful if you describe the exact location in the Comments section)

Any other information, such as interesting behavior

Go to: www.reportband.gov, click Continue (instructions will continue in English, or you may select one of the other available languages)

Select I am the finder

Report as Color Marker Only, click Continue

For species, type in Turkey Vulture

Select the other encounter information from the drop-downs – How Obtained will most likely be “Saw or photographed…other marker while bird was free” (but there are other options available if needed). If you noticed a symbol on the tag, such as a dot below the numbers, you will need to include that detail in the Comments section, as only alpha & numeric characters can be entered in the code box.

Click Continue after finishing each section to move to the next tab. Enter as much information as you are able. If any required info is missing, the website will flag the missing data. You are also able to send a photo after you submit your report.

If the tag is white with a black code, feel free to click here to send a note and/or photos to us – these photos help show us how the tags appear over time, as well as document the condition of the vulture. Occasionally Pete may use our database photos in educational presentations or handouts, with permission; if you send us a photo, please let us know if it is ok to use your photo for these types of purposes (photographer credit is given unless anonymous is preferred). We understand if you would prefer that your photos not be used publicly - your photos will still be stored in the database, but will be kept separate for internal reference only.

If you have sent us one of those emails and/or photos, THANK YOU!! You have contributed an important data point to our 20+ year ongoing research project, which includes monitoring lead toxicity as well as migratory and dispersal patterns in Turkey Vultures. Without these publicly reported sightings, our data set would be very small and so much less informative.

Hopefully you have learned something new, and maybe even gained an appreciation for the amazing bird that is the Turkey Vulture. With bird-watching and long-lens camera photography gaining popularity as outdoor activities, we expect to continue to receive more and more reports of tagged vultures. Maybe now, you will find yourself looking a little closer at any large black bird you see soaring over your head.

Bloom RESEARCH:

Pete Bloom and his colleagues’ current research typically focuses on the health and movements of Turkey Vultures. We have had five peer-reviewed articles published on these topics (see below) since 2011. Most studies take several years to gather and then analyze the data.

Dr. Miguel D. Saggese (DVM), an Associate Professor at Western U, in Pomona, CA has been working with Pete for many years studying vultures, especially with the ongoing lead research. Several graduate students, including Alexandra Eagleton, Alexandria Koedel, and Ella Eleopoulos, have worked with Pete along with their advisor Andrea Bonisoli Alquati, (Ph.D.) at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. Blood and other biological samples are collected and used to analyze blood lead levels, rodenticide exposure, and overall health.

The research into Turkey Vulture movements include topics such as natal dispersal (where do birds go when they fledge?), breeding dispersal (where do birds end up when it is time to breed and raise young, and does it differ from year to year?), as well as migration (are there seasonal movements between regions?).

Bloom, P. H., Overby, N., Saggese, M. D., Eagleton, A., Koedel, A. B., Batzloff, H., & Bonisoli-Alquati, A. (2025). Movements of Turkey Vultures Provide Evidence of Nonmigratory Behavior and Natal Philopatry in a Population Breeding in Southwestern California, USA. Journal of Raptor Research, 59(4):jrr2392.

Saggese, M. D., Bloom, P. H., Bonisoli-Alquati, A., Kinyon, G., Overby, N., Koedel, A., ... & Poppenga, R. H. (2024). Turkey Vultures (Cathartes aura) from Southern California are Exposed to Anticoagulant Rodenticides Despite Recent Bans. Journal of Raptor Research, 58(4), 491-498.

Oakley, B. B., Melgarejo, T., Bloom, P. H., Abedi, N., Blumhagen, E., & Saggese, M. D. (2021). Emerging pathogenic Gammaproteobacteria Wohlfahrtiimonas chitiniclastica and Ignatzschineria species in a Turkey Vulture (Cathartes aura). Journal of Avian Medicine and Surgery, 35(3), 280-289.

Bloom, P. H., Papp, J. M., Saggese, M. D., & Gresham, A. M. (2019). A simple, effective and portable modified walk-in turkey vulture trap. North American Bird Bander, 44(4), 5.

Kelly, T. R., Bloom, P. H., Torres, S. G., Hernandez, Y. Z., Poppenga, R. H., Boyce, W. M., & Johnson, C. K. (2011). Impact of the California lead ammunition ban on reducing lead exposure in golden eagles and turkey vultures. PLoS One, 6(4), e17656.

Houston C. S., Bloom P. H. 2005. Turkey vulture marking history: The switch from leg bands to patagial tags. North American Bird Bander, 30(2), 59–64.

Henckel, R. E. (1976). Turkey Vulture banding problem. North American bird bander, 1(3), 7.

Photos above by Pete Bloom (all rights reserved) with the exception of the final image of “LA” in Yuma, used with permission by the photographer.

Historical RESEARCH

Turkey Vulture, California Condor, and Common Ravens at a carcass (Photo Credit: Pete Bloom - all rights reserved)

Photo credit: Ryan Wood (Orange County, CA) - all rights reserved, used with permission.

During the 1980’s, Pete Bloom led the Condor Research Team, working to save wild California Condors. Since lead ammunition was a known cause of poisoning in condors, a suitable ammunition replacement needed to be found; two possibilities were copper and tungsten-tin-bismuth (TTB). In 1997, graduate student Ramon Valencia from California State University Long Beach, with the help of several advisors (including Pete Bloom), arranged a study where 30 Turkey Vultures were trapped and kept in captivity under veterinary care for a period of six months, to evaluate the potential effects of these lead-replacement materials, using two test groups compared to a control group. His study revealed that CBC and chemistry panels had no significant differences, and no cellular toxicity was found between the control and test groups. Copper was found not to concentrate in the blood sera, although tin concentrations became elevated for those treated with TTB. All of the Turkey Vultures used in the study were tagged with Bloom’s white patagial tags showing a black two-digit code before being released at the end of the study period. At least one Turkey Vulture from this 1997 study was known to still be alive as of 2019, as shown in the photo to the right. The tag was able to definitively identify and age this bird, which is why these markers are so important to research, and the sightings of these markers reported by the public are also incredibly important and appreciated.

Dissertation: Valencia, R. M. (2003). An assessment of the toxicological effects of ingested copper and tungsten-tin-composite (TTC) bullets on the California condor (Gymnogyps californianus) using the turkey vulture (Cathartes aura) as a surrogate species. California State University, Long Beach.

You may notice some similarities between this page and a blog article on the Bloom Biological, Inc. website. Bloom Biological Inc. was Pete Bloom’s biological consulting company, which is now a part of the Endemic Environmental Services family. “By uniting Bloom’s legacy with Endemic, ICRE, and Cambriate, the partnership strengthens Endemic’s mission of Conservation at Scale through science, mentorship, and innovative research.”